Potawatomi Point, Indiana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western

The Potawatomi are first mentioned in French records, which suggests that in the early 17th century, they lived in what is now southwestern

The Potawatomi are first mentioned in French records, which suggests that in the early 17th century, they lived in what is now southwestern

*

*

Several bands of Potawatomi are active.

Several bands of Potawatomi are active.

Hannahville Indian Community; Wilson, MI

Citizen Potawatomi Nation

official website

Forest County Potawatomi

Kettle & Stony Point First Nation

Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi

(Gun Lake)

Moose Deer Point First Nation

Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

Potawatomi Author Larry Mitchell

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

Treaty Between the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi Indians

Potawatomi Migration from Wisconsin and Michigan to Canada

{{authority control Algonquian peoples Great Lakes tribes Native American tribes in Kansas Native American tribes in Illinois Native American tribes in Michigan Native American tribes in Wisconsin Native American tribes in Oklahoma Algonquian ethnonyms Native American tribes in Indiana Native American tribes in Nebraska

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

region, upper Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language

Potawatomi (, also spelled Pottawatomie; in Potawatomi Bodwéwadmimwen, or Bodwéwadmi Zheshmowen, or Neshnabémwen) is a Central Algonquian language. It was historically spoken by the Pottawatomi people who lived around the Great Lakes in wha ...

, a member of the Algonquin family. The Potawatomi call themselves ''Neshnabé'', a cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymology, etymological ancestor in a proto-language, common parent language. Because language c ...

of the word ''Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabeg (adjectival: Anishinaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples present in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe (including Saulteaux and Oji-Cree), Odawa, Potawatomi, ...

''. The Potawatomi are part of a long-term alliance, called the Council of Three Fires

The Council of Three Fires (in oj, label=Anishinaabe, Niswi-mishkodewinan, also known as the People of the Three Fires; the Three Fires Confederacy; or the United Nations of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians) is a long-standing Anishina ...

, with the Ojibway

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

and Odawa (Ottawa). In the Council of Three Fires, the Potawatomi are considered the "youngest brother" and are referred to in this context as ''Bodwéwadmi'', a name that means "keepers of the fire" and refers to the council fire of three peoples.

In the 18th century, they were pushed to the west by European/American encroachment and eventually removed from their lands in the Great Lakes region to reservations in Oklahoma. Under Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

, they eventually ceded many of their lands, and most of the Potawatomi relocated to Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, and Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

. Some bands survived in the Great Lakes region and today are federally recognized as tribes. In Canada, over 600 First Nation

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

governments or bands are recognized. In the US, 574 tribes or bands are federally recognized.

Name

The English "Potawatomi" is derived from theOjibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

( syncoped in the Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

as ). The Potawatomi name for themselves (autonym

Autonym may refer to:

* Autonym, the name used by a person to refer to themselves or their language; see Exonym and endonym

* Autonym (botany), an automatically created infrageneric or infraspecific name

See also

* Nominotypical subspecies, in zo ...

) is (without syncope: ; plural: ), a cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymology, etymological ancestor in a proto-language, common parent language. Because language c ...

of the Ojibwe form. Their name means "those who tend the hearth-fire," which refers to the hearth of the Council of Three Fires

The Council of Three Fires (in oj, label=Anishinaabe, Niswi-mishkodewinan, also known as the People of the Three Fires; the Three Fires Confederacy; or the United Nations of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians) is a long-standing Anishina ...

. The word comes from "to tend the hearth-fire", which is (without syncope: ) in the Potawatomi language

Potawatomi (, also spelled Pottawatomie; in Potawatomi Bodwéwadmimwen, or Bodwéwadmi Zheshmowen, or Neshnabémwen) is a Central Algonquian language. It was historically spoken by the Pottawatomi people who lived around the Great Lakes in wha ...

; the Ojibwe and Ottawa forms are and , respectively.

Alternatively, the Potawatomi call themselves (without syncope: ; plural: ), a cognate of Ojibwe , meaning "original people".

Teachings

The Potawatomi teach their children about the "Seven Grandfather Teachings" of wisdom, respect, love, honesty, humility, bravery, and truth toward each other and all creation, each one of which teaches them the equality and importance of their fellow tribesmen and respect for all of nature’s creations. The story itself teaches the importance of patience and listening, as it follows the Water Spider's journey to retrieve fire for the other animals to survive the cold. As the other animals step forth one after another to proclaim that they shall be the ones to retrieve the fire, the Water Spider sits and waits while listening to her fellow animals. As they finish and wrestle with their fears, she steps forward and announces that she will be the one to bring it back. As they laugh and doubt her, she weaves a bowl out of her own web that sails her across the water to retrieve the fire. She brings back a hot coal out of which they make fire, and they celebrate her honor and bravery.History

The Potawatomi are first mentioned in French records, which suggests that in the early 17th century, they lived in what is now southwestern

The Potawatomi are first mentioned in French records, which suggests that in the early 17th century, they lived in what is now southwestern Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

. During the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

, they fled to the area around Green Bay to escape attacks by both the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and the Neutral Nation

The Neutral Confederacy (also Neutral Nation, Neutral people, or ''Attawandaron'' by neighbouring tribes) were an Iroquoian people who lived in what is now southwestern and south-central Ontario in Canada, North America. They lived throughout ...

, who were seeking expanded hunting grounds. In 1658, the Potawatomi were estimated to number around 3,000.

As an important part of Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

's Confederacy, Potawatomi warriors took part in Tecumseh's War

Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion was a conflict between the United States and Tecumseh's Confederacy, led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh in the Indiana Territory. Although the war is often considered to have climaxed with William Henry Har ...

, the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

and the Peoria War

During the War of 1812, the Illinois Territory was the scene of fighting between Native Americans and United States soldiers and settlers. The Illinois Territory at that time included the areas of modern Illinois, Wisconsin and parts of Minneso ...

. Their alliances switched repeatedly between Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and the United States, as power relations shifted between the nations, and they calculated effects on their trade and land interests.

At the time of the War of 1812, a band of Potawatomi inhabited the area near Fort Dearborn

Fort Dearborn was a United States fort built in 1803 beside the Chicago River, in what is now Chicago, Illinois. It was constructed by troops under Captain John Whistler and named in honor of Henry Dearborn, then United States Secretary of War. ...

, where Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

developed. Led by the chiefs Blackbird and Nuscotomeg (Mad Sturgeon), a force of about 500 warriors attacked the United States evacuation column leaving Fort Dearborn; they killed most of the civilians and 54 of Captain Nathan Heald

Nathan Heald (New Ipswich, New Hampshire September 24, 1775 – O'Fallon, Missouri April 27, 1832) was an officer in the U.S. Army, during the War of 1812. He was in command of Fort Dearborn in Chicago during the Battle of Fort Dearborn.

Heald w ...

's force and wounded many others. George Ronan

Ensign George Ronan was a commissioned officer of the United States Army. Educated at West Point and commissioned as an officer in the 1st Infantry Regiment in 1811, he was assigned to duty at Fort Dearborn, a frontier post at the mouth of the ...

, the first graduate of West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

to be killed in combat, died in this ambush. The incident is referred to as the "Fort Dearborn Massacre

The Battle of Fort Dearborn (sometimes called the Fort Dearborn Massacre) was an engagement between United States troops and Potawatomi Native Americans that occurred on August 15, 1812, near Fort Dearborn in what is now Chicago, Illinois (at that ...

". A Potawatomi chief named Mucktypoke (, Black Pheasant), counseled his fellow warriors against the attack. Later he saved some of the civilian captives who were being ransomed by the Potawatomi.

French period (1615–1763)

TheFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

period of contact began with early explorers who reached the Potawatomi in western and northern Michigan. They also found the tribe located along the Door Peninsula

The Door Peninsula is a peninsula in eastern Wisconsin, separating the southern part of the Green Bay (Lake Michigan), Green Bay from Lake Michigan. The peninsula includes northern Kewaunee County, Wisconsin, Kewaunee County, northeaster ...

of Wisconsin. By the end of the French period, the Potawatomi had begun a move to the Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

area, leaving the large communities in Wisconsin. The French helped to solidify their alliance with the Potawatomi by helping them raid numerous Sauk villages and Fox villages in the early 1700s as well as by compelling the Kickapoo nation to make many concessions to the Potawatomi.

* Madouche during the Fox Wars

The Fox Wars were two conflicts between the French and the Fox (Meskwaki or Red Earth People; Renards; Outagamis) Indians that lived in the Great Lakes region (particularly near the Fort of Detroit) from 1712 to 1733.In their book ''The Fox Wars ...

* Millouisillyny

* Onanghisse (''Wnaneg-gizs'' "Shimmering Light") at Green Bay

* Otchik at Detroit

British period (1763–1783)

The British period of contact began when France ceded its lands after the defeat in theFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

(or Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

). Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

was an attempt by Native Americans to push the British and other European settlers out of their territory. The Potawatomi captured every British frontier garrison but the one at Detroit.

The Potawatomi nation continued to grow and expanded westward from Detroit, most notably in the development of the St. Joseph villages adjacent to the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

in southwestern Michigan. The Wisconsin communities continued and moved south along the Lake Michigan shoreline.

* Nanaquiba (Water Moccasin) at Detroit

* Ninivois at Detroit

* Peshibon at St. Joseph

Joseph (; el, Ἰωσήφ, translit=Ioséph) was a 1st-century Jewish man of Nazareth who, according to the canonical Gospels, was married to Mary, the mother of Jesus, and was the legal father of Jesus. The Gospels also name some brothers ...

* Washee (from , "the Swan") at St. Joseph during Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

United States treaty period (1783–1830)

The United States treaty period of Potawatomi history began with theTreaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of George III, King George III of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and representatives of the United States, United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the Ame ...

, which ended the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

and established the United States' interest in the lower Great Lakes. It lasted until the treaties for Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

were signed. The US recognized the Potawatomi as a single tribe. They often had a few tribal leaders whom all villages accepted. The Potawatomi had a decentralized society, with several main divisions based on geographic locations: Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

or Wisconsin area, Detroit or Huron River

The Huron River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed November 7, 2011 river in southeastern Michigan, rising out of the Huron Swamp in Springfield Township in north ...

, the St. Joseph River, the Kankakee River

The Kankakee River is a tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long, in the Central Corn Belt Plains of northwestern Indiana and northeastern Illinois in the United States. At one time, the river drained one of the largest wetlands in N ...

, Tippecanoe and Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

s, the Illinois River

The Illinois River ( mia, Inoka Siipiiwi) is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River and is approximately long. Located in the U.S. state of Illinois, it has a drainage basin of . The Illinois River begins at the confluence of the D ...

and Lake Peoria, and the Des Plaines

Des Plaines is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States. Per the 2020 census, the population was 60,675. The city is a suburb of Chicago and is located just north of O'Hare International Airport. It is situated on and is named after the ...

and Fox Rivers.

The chiefs listed below are grouped by geographic area.

Milwaukee Potawatomi

* Manamol * Siggenauk (: "Le Tourneau" or "Blackbird")Chicago Potawatomi

*Billy Caldwell

Billy Caldwell, baptized Thomas Caldwell (March 17, 1782 – September 28, 1841), known also as ''Sauganash'' ( ne who speaksEnglish), was a British-Potawatomi fur trader who was commissioned captain in the Indian Department of Canada duri ...

, also known as Sauganash

Billy Caldwell, baptized Thomas Caldwell (March 17, 1782 – September 28, 1841), known also as ''Sauganash'' ( ne who speaksEnglish), was a British-Potawatomi fur trader who was commissioned captain in the Indian Department of Canada duri ...

(''Zhaaganaash'': "Englishman") (1780–1841)

Des Plaines and Fox River Potawatomi

* Aptakisic (, "Half Day") * Mukatapenaise ( "Blackbird") *Waubonsie

Waubonsie (c. 1760 – c. 1848) was a leader of the Potawatomi Native American people. His name has been spelled in a variety of ways, including Wabaunsee, Wah-bahn-se, Waubonsee, ''Waabaanizii'' in the contemporary Ojibwe language, and ''Wabanz ...

(He Causes Paleness)

* Waweachsetoh along with La Gesse, Gomo, or Masemo (Resting Fish)

Illinois River Potawatomi

* Mucktypoke (: "Black Partridge") *Senachewine

Senachwine (Potawatomi language, Potawatomi: ''Znajjewan'', "Difficult Current") or Petchaho (supposedly from Potawatomi: "Red Cedar") (c. 1744-1831) was a 19th-century Illinois River Potawatomi chieftain. In 1815, he succeeded his brother Chief ...

( 1831) (Petacho or "Difficult Current") was the brother of Gomo, who was chief among the Lake Peoria Potawatomi

Kankakee River (Iroquois and Yellow Rivers) Potawatomi

*Main Poc Main Poc (1768–1816), also recorded as Main Poche, Main Pogue, Main Poque, Main Pock; supposedly from the French, meaning "Crippled Hand", was a leader of the Yellow River villages of the Potawatomi Native Americans in the United States. Through ...

, also known as Webebeset ("Crafty One")

* Micsawbee 19th century

* Notawkah (Rattlesnake) on the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Standard Beijing Mandarin, Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system in the world at th ...

* Nuscotomeg (, "Mad Sturgeon") on the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and Kankakee River

The Kankakee River is a tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long, in the Central Corn Belt Plains of northwestern Indiana and northeastern Illinois in the United States. At one time, the river drained one of the largest wetlands in N ...

s

* Mesasa (, "Turkey Foot")

St. Joseph and Elkhart Potawatomi

* Chebass (: "Little Duck") on the St. Joseph River *Five Medals

Five Medals (; also recorded as Wonongaseah or Wannangsea, from the Potawatomi ''Wa-nyano-zhoneya'', "Five-coin" or "Five-medal") was a leader of the Elkhart River Potawatomi. He led his people in defense of their homelands and was a proponent of ...

(: "Five-coin") on the Elkhart River

The Elkhart River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 19, 2011 tributary of the St. Joseph River in northern Indiana in the United States. It is almost entirely c ...

* Onaska on the Elkhart River

The Elkhart River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 19, 2011 tributary of the St. Joseph River in northern Indiana in the United States. It is almost entirely c ...

* Topinbee (He who sits Quietly) ( 1826)

Tippecanoe and Wabash River Potawatomi

* Aubenaubee (1761–1837/8) on theTippecanoe River

The Tippecanoe River ( ) is a gentle, U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 19, 2011 river in the Central Corn Belt Plains ecoregion in northern Indiana. It flows from Croo ...

* Askum (More and More) on the Eel River

* George Cicott

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

(1800?–1833)

* Keesass on the Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

* Kewanna (1790?–1840s?) (Prairie Chicken) Eel River

* Kinkash (see Askum)

* Magaago

* Monoquet (1790s–1830s) on the Tippecanoe River

The Tippecanoe River ( ) is a gentle, U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 19, 2011 river in the Central Corn Belt Plains ecoregion in northern Indiana. It flows from Croo ...

* Tiosa on the Tippecanoe River

The Tippecanoe River ( ) is a gentle, U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 19, 2011 river in the Central Corn Belt Plains ecoregion in northern Indiana. It flows from Croo ...

* Winamac

Winamac was the name of a number of Potawatomi leaders and warriors beginning in the late 17th century. The name derives from a man named Wilamet, a Native American from an eastern tribe who in 1681 was appointed to serve as a liaison between New ...

(, "Catfish")—allied with the British during the War of 1812

* Winamac

Winamac was the name of a number of Potawatomi leaders and warriors beginning in the late 17th century. The name derives from a man named Wilamet, a Native American from an eastern tribe who in 1681 was appointed to serve as a liaison between New ...

(, "Catfish")—allied with the Americans during the War of 1812

Fort Wayne Potawatomi

*

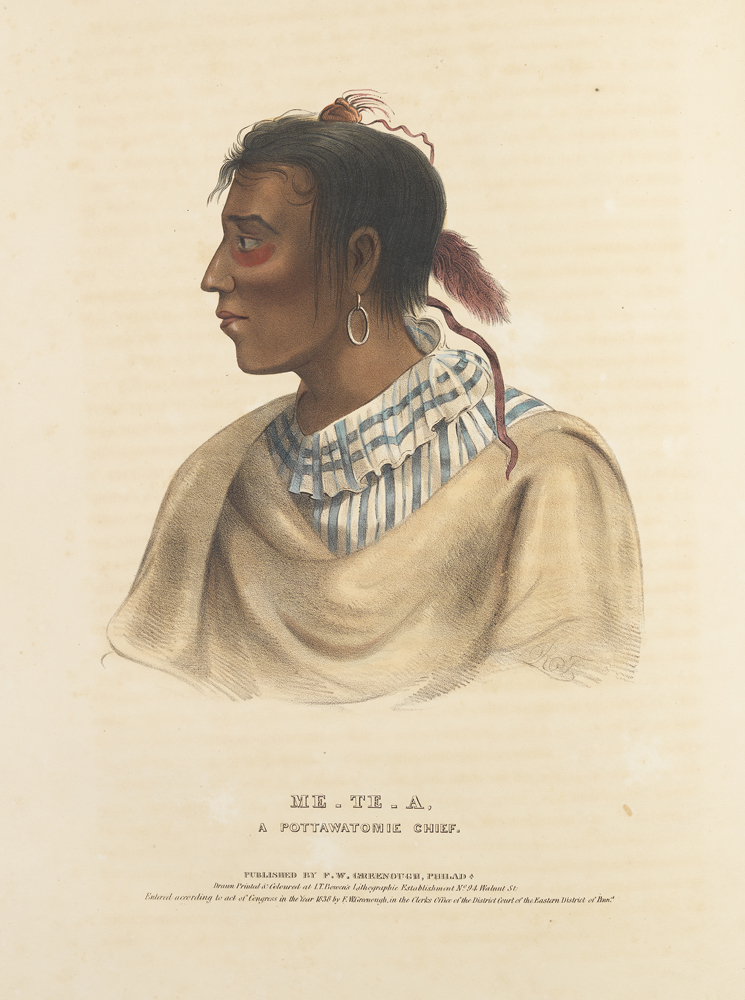

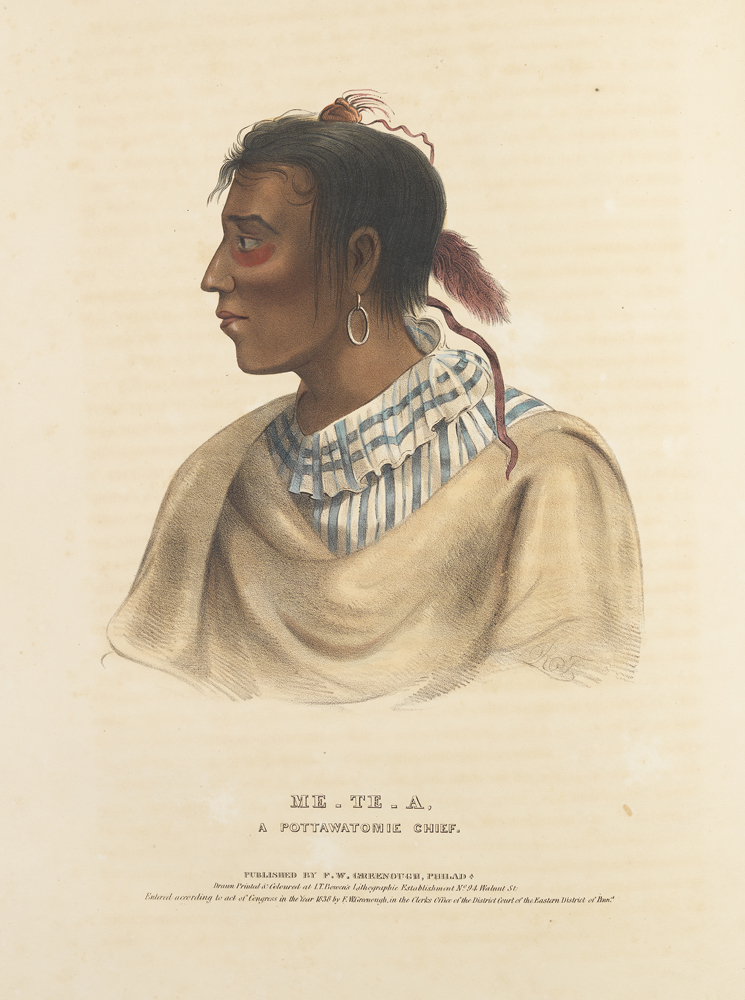

* Metea

Chief Metea or Me-te-a ( fl. 1812–1827) (Potawatomi: ''Mdewé'' "Sulks") was one of the principal chiefs of the Potawatomi during the early 19th century. He frequently acted as spokesman at treaty councils. His village, Muskwawasepotan, was ...

(1760?–1827) (, "Sulks")

* Wabnaneme on the Pigeon River

American removal period (1830–1840)

The removal period of Potawatomi history began with the treaties of the late 1820s when the United States created reservations.Billy Caldwell

Billy Caldwell, baptized Thomas Caldwell (March 17, 1782 – September 28, 1841), known also as ''Sauganash'' ( ne who speaksEnglish), was a British-Potawatomi fur trader who was commissioned captain in the Indian Department of Canada duri ...

and Alexander Robinson negotiated for the United Nations of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potowatomi in the Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien

The Treaty of Prairie du Chien may refer to any of several treaties made and signed in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin between the United States, representatives from the Sioux, Sac and Fox, Menominee, Ioway, Winnebago and the Anishinaabeg ( Chippew ...

(1829), by which they ceded most of their lands in Wisconsin and Michigan. Some Potawatomi became religious followers of the "Kickapoo Prophet", Kennekuk

Keannekeuk (c. 1790–1852), also known as the "Kickapoo Prophet", was a Kickapoo medicine man and spiritual leader of the Vermilion band of the Kickapoo nation. He lived in East Central Illinois much of his life along the Vermilion River. One s ...

. Over the years, the US reduced the size of the reservations under pressure for land by invading European Americans.

The final step followed the 1833 Treaty of Chicago

The 1833 Treaty of Chicago struck an agreement between the United States government that required the Chippewa Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes cede to the United States government their of land (including reservations) in Illinois, the Wiscon ...

, negotiated for the tribes by Caldwell and Robinson. In return for land cessions, the US promised new lands, annuities, and supplies to enable the peoples to develop new homes. The Illinois Potawatomi were removed to Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

and the Indiana Potawatomi to Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, both west of the Mississippi River. Often, annuities and supplies were reduced or late in arrival, and the Potawatomi suffered after their relocations. Those in Kansas later were removed to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

, now Oklahoma. The removal of the Indiana Potawatomi was documented by a Catholic priest, Benjamin Petit

Benjamin Marie Petit (April 8, 1811 – February 10, 1839) was a Catholic missionary to the Potawatomi at Twin Lakes, Indiana,

where he served from November 1837 to September 1838. A native of Rennes in Brittany, France, Petit was trained ...

, who accompanied the Indians on the Potawatomi Trail of Death

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of about 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers Lake and Cook ...

. Petit died while returning to Indiana. His diary was published in 1941 by the Indiana Historical Society.

Many Potawatomi found ways to remain, primarily those in Michigan. Others fled to their Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ), said to mean "traders", are an Indigenous American ethnic group who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, commonly known as the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. They ha ...

neighbors or to Canada to avoid removal to the west.

* ''Iowa'', Wabash River

The Wabash River ( French: Ouabache) is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 river that drains most of the state of Indiana in the United States. It flows fro ...

* ''Maumksuck'' (, "Big Foot") at Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial lak ...

* ''Mecosta Mecosta was a 19th-century Potawatomi chief. His name in the Potawatomi language was ''Mkozdé'', meaning "Having a Bear's Foot" but the name was recorded in English to mean "Big Bear."

'' (, "Having a Bear's Foot")

* Chief Menominee

Menominee (c. 1791 – April 15, 1841) was a Potawatomi chief and religious leader whose village on reservation lands at Twin Lakes, southwest of Plymouth in present-day Marshall County, Indiana, became the gathering place for the Potawatomi w ...

(1791?–1841) Twin Lakes of Marshall County

* ''Pamtipee'' of Nottawasippi

* ''Mackahtamoah'' (, "Black Wolf") of Nottawasippi

* ''Pashpoho'' of Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Standard Beijing Mandarin, Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system in the world at th ...

near Rochester, Indiana

Rochester is a city in, and the county seat of, Fulton County, Indiana, United States. The population was 6,218 at the 2010 census.

History

Rochester was laid out in 1835. The founder Alexander Chamberlain named it for his former hometown of R ...

* ''Pepinawah''

* Leopold Pokagon

Leopold Pokagon (c. 1775 – 1841) was a Potawatomi ''Wkema'' (leader). Taking over from Topinbee, who became the head of the Potawatomi of the Saint Joseph River Valley in Michigan, a band that later took his name.

Early life and education

Po ...

(–1841)

* Simon Pokagon

Simon Pokagon ( 1830- January 28, 1899) was a member of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, an author, and a Native American advocate. He was born near Bertrand in southwest Michigan Territory and died on January 28, 1899 in Hartford, Michig ...

(–1899)

* ''Sauganash

Billy Caldwell, baptized Thomas Caldwell (March 17, 1782 – September 28, 1841), known also as ''Sauganash'' ( ne who speaksEnglish), was a British-Potawatomi fur trader who was commissioned captain in the Indian Department of Canada duri ...

'' (Billy Caldwell) removed his band ultimately to what would become Council Bluffs, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha–Council Bluffs ...

in 1838, where they lived at what was known as Caldwell's Camp. Father Pierre-Jean De Smet

Pierre-Jean De Smet, SJ ( ; 30 January 1801 – 23 May 1873), also known as Pieter-Jan De Smet, was a Flemish Catholic priest and member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He is known primarily for his widespread missionary work in the mid-19th ...

established a mission there that was active 1837-1839.

* ''Shupshewahno'' (19th century – 1841) or (Vision of a Lion) at Shipshewana

Shipshewana is a town in Newbury Township, LaGrange County, Indiana, United States. The population was 658 at the 2010 census. It is the location of the Menno-Hof Amish & Mennonite Museum, which showcases the history of the Amish and Mennonite p ...

Lake.

* ''Topinbee'' (The Younger) on the St. Joseph River

* ''Wabanim'' (, "White Dog") on the Iroquois River

* (Snapping Turtle) on the Iroquois River

* ''Wanatah''

* ''Weesionas'' (see Ashkum)

* ''Wewesh''

Bands

Several bands of Potawatomi are active.

Several bands of Potawatomi are active.

United States

Federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

Potawatomi tribes in the United States:

* Citizen Potawatomi Nation

Citizen Potawatomi Nation is a federally recognized tribe of Potawatomi people located in Oklahoma. The Potawatomi are traditionally an Algonquian-speaking Eastern Woodlands tribe. They have 29,155 enrolled tribal members, of whom 10,312 live in ...

(Shishibéniyék), Oklahoma

* Forest County Potawatomi Community

The Forest County Potawatomi Community ( pot, Ksenyaniyek) is a federally recognized tribe of Potawatomi people with approximately 1,400 members as of 2010. The community is based on the Forest County Potawatomi Indian Reservation, which cons ...

(Ksenyaniyék), Wisconsin

* Hannahville Indian Community

The Hannahville Indian Community is a federally recognized Potawatomi tribe residing in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, approximately west of Escanaba on a reservation. The reservation, at , lies mostly in Harris Township in eastern Menominee Cou ...

(Wigwas zibiwniyék), Michigan

* Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band

The Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians of Michigan is a federally recognized tribe of Potawatomi people in Michigan named for a 19th-century Ojibwe chief. They were formerly known as the Gun Lake Band of Grand River Ottawa Indi ...

of Pottawatomi (also known as the Gun Lake tribe) (Mthebnéshiniyêk), based in Dorr Dorr may refer to:

* Dorr (surname)

* Dorr, Iran, a village in Isfahan Province, Iran

* Dorr Township, McHenry County, Illinois

* Dorr Township, Michigan

** Dorr, Michigan

See also

* Door (disambiguation)

* Dorr Rebellion

* Wilmer Cutler P ...

in Allegan County, Michigan

Allegan County ( ) is a Counties of the United States, county in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 120,502. The county seat is Allegan, Michigan, Allegan. The name was coined by Henry Rowe School ...

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

The Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (NHBP) is a federally-recognized tribe of Potawatomi in the United States. The tribe achieved federal recognition on December 19, 1995, and currently has approximately 1500 members.

The Pine Creek India ...

(Nadwézibiniyêk), based in Calhoun County, Michigan

Calhoun County is a county in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 134,310. The county seat is Marshall. The county was established on October 19, 1829, and named after John C. Calhoun, who was at the time Vice ...

* Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians ( Potawatomi: Pokégnek Bodéwadmik) are a federally recognized Potawatomi-speaking tribe based in southwestern Michigan and northeastern Indiana. Tribal government functions are located in Dowagiac, Michigan. ...

(Pokégnek Bodéwadmik), Michigan and Indiana

* Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation ( pot, Mshkodéniwek, formerly the Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians) is a federally recognized tribe of Neshnabé (Potawatomi people), headquartered near Mayetta, Kansas.

History

The ''Mshkodésik'' ("People of t ...

(Mshkodéniwék ), Kansas

Canada - First Nations with Potawatomi people

*Caldwell First Nation

The Caldwell First Nation ( oj, Zaaga'iganiniwag, ''meaning: "people of the Lake"'') is a First Nations band government whose land base is located in Leamington, Ontario, Canada. They are an Anishinaabe group, part of the Three Fires Confederacy, ...

(Zaaga'iganiniwag), Point Pelee

Point Pelee National Park (; french: Parc national de la Pointe-Pelée) is a national park in Essex County in southwestern Ontario, Canada where it extends into Lake Erie. The word is French for 'bald'. Point Pelee consists of a peninsula of la ...

and Pelee Island Pelee may refer to:

* Île Pelée, an island off Cherbourg-en-Cotentin, France

*Pelee, Ontario, an island in Lake Erie, Canada

*Point Pelee National Park, a park in Ontario, Canada

*Mount Pelée, a volcano in Martinique

*Peleus

In Greek mytholo ...

, Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

* Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation

Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation ( oj, Neyaashiinigmiing Anishinaabek) is an Anishinaabek First Nation from the Bruce Peninsula region in Ontario, Canada. Along with the Saugeen First Nation, they form the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. The Chi ...

(Neyaashiinigmiing), Bruce Peninsula

The Bruce Peninsula is a peninsula in Ontario, Canada, that divides Georgian Bay of Lake Huron from the lake's main basin. The peninsula extends roughly northwestwards from the rest of Southwestern Ontario, pointing towards Manitoulin Islan ...

, Ontario

* Saugeen First Nation

Saugeen First Nation ( oj, Saukiing) is an Ojibway First Nation band located along the Saugeen River and Bruce Peninsula in Ontario, Canada. The band states that their legal name is the "Chippewas of Saugeen". Organized in the mid-1970s, Saugeen ...

(Saukiing), Ontario (Bruce Peninsula

The Bruce Peninsula is a peninsula in Ontario, Canada, that divides Georgian Bay of Lake Huron from the lake's main basin. The peninsula extends roughly northwestwards from the rest of Southwestern Ontario, pointing towards Manitoulin Islan ...

)

* Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point

Kettle & Stony Point First Nation ( oj, Wiiwkwedong Anishinaabek, meaning: "in/at the bay") comprises the Kettle Point reserve and Stony Point Reserve (which is under remedial cleanup after over 50 years of occupation by the Canadian Armed Forces), ...

(Wiiwkwedong), Ontario

* Moose Deer Point First Nation

Moose Deer Point First Nation is a Potawatomi First Nation in the District Municipality of Muskoka, Ontario. It has a reserve called Moose Point 79. The reserve is located along Twelve Mile Bay.

The First nation is a member of the Anishinabek N ...

, Ontario

* Walpole Island First Nation

Walpole Island is an island and First Nation reserve in southwestern Ontario, Canada, on the border between Ontario and Michigan in the United States. It is located in the mouth of the St. Clair River on Lake St. Clair, about by road from Wind ...

(Bkejwanong) on an unceded island between the United States and Canada

* Wasauksing First Nation

Wasauksing First Nation (formerly named as Parry Island First Nation, oj, Waaseyakosing, ''meaning: "Place that shines brightly in the reflection of the sacred light"'') is an Ojibway, Odawa and Pottawatomi First Nation band government whose res ...

(Waaseyakosing), Parry Island, Ontario

Population

Clans

La Chauvignerie (1736) and Morgan (1877) mention among the Potawatomidoodem

The Anishinaabe, like most Algonquian-speaking groups in North America, base their system of kinship on patrilineal clans or totems. The Ojibwe word for clan () was borrowed into English as totem

A totem (from oj, ᑑᑌᒼ, italics=no o ...

s (clans) being:

* ''Bené'' (Turkey)

* ''Gagagshi'' (Crow)

* ''Gnew'' (Golden Eagle)

* ''Jejakwe (Thunderer, i.e. Crane)

* ''Mag'' (Loon)

* ''Mekchi'' (Frog)

* ''Mek'' (Beaver)

* ''Mewi'a'' (Wolf)

* ''Mgezewa'' (Bald Eagle)

* ''Mkedésh-gékékwa'' (Black Hawk)

* ''Mko'' (Bear)

* ''Mshéwé'' (Elk)

* ''Mshike (Turtle)

* ''Nme (Sturgeon)

* ''Nmébena'' (Carp)

* ''Shage'shi'' (Crab)

* ''Wabozo'' (Rabbit)

* ''Wakeshi'' (Fox)

Ethnobotany

They regard ''Epigaea repens

''Epigaea repens'', the mayflower, trailing arbutus, or ground laurel, is a low, spreading shrub in the family Ericaceae. It is found from Newfoundland to Florida, west to Kentucky and the Northwest Territories.

Description

The plant is a slow-g ...

'' as their tribal flower and consider it to have come directly from their divinity. ''Allium tricoccum

''Allium tricoccum'' (commonly known as ramp, ramps, ramson, wild leek, wood leek, or wild garlic) is a North American species of wild onion or garlic widespread across eastern Canada and the eastern United States. Many of the common English na ...

''is consumed in traditional Potawatomi cuisine. They mix an infusion

Infusion is the process of extracting chemical compounds or flavors from plant material in a solvent such as water, oil or alcohol, by allowing the material to remain suspended in the solvent over time (a process often called steeping). An inf ...

of the root of ''Uvularia grandiflora

''Uvularia grandiflora'', the large-flowered bellwort or merrybells, is a species of flowering plant in the family (biology), family Colchicaceae, native plant, native to eastern and central North America.

Description

Growing to tall by broad ...

'' with lard and use it as salve to massage sore muscles and tendons. They use ''Symphyotrichum novae-angliae

(formerly ''Aster novae-angliae'') is a species of flowering plant in the aster family (Asteraceae) native to central and eastern North America. Commonly known as , , or , it is a perennial, herbaceous plant usually between tall and wide ...

'' as a fumigating reviver. ''Vaccinium myrtilloides

''Vaccinium myrtilloides'' is a shrub with common names including common blueberry, velvetleaf huckleberry, velvetleaf blueberry, Canadian blueberry, and sourtop blueberry. It is common in much of North America, reported from all 10 Canadian prov ...

'' is part of their traditional cuisine, and is eaten fresh, dried, and canned. They also use the root bark of the plant for an unspecified ailment. The Potawatomi use the needles of ''Abies balsamea

''Abies balsamea'' or balsam fir is a North American fir, native to most of eastern and central Canada (Newfoundland west to central Alberta) and the northeastern United States (Minnesota east to Maine, and south in the Appalachian Mountains to ...

'' to make pillows, believing that the aroma prevented one from getting a cold.Smith, Huron H., 1933, Ethnobotany of the Forest Potawatomi Indians, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 7:1-230, page 121 They also use the balsam gum of ''Abies balsamea

''Abies balsamea'' or balsam fir is a North American fir, native to most of eastern and central Canada (Newfoundland west to central Alberta) and the northeastern United States (Minnesota east to Maine, and south in the Appalachian Mountains to ...

'' as a salve for sores, and take an infusion of the bark for tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and other internal afflictions.

Location

The Potawatomi first lived in lower Michigan, then moved to northern Wisconsin, and eventually settled into northern Indiana and central Illinois. In the early 19th century, major portions of Potawatomi lands were seized by the U.S. government. Following the Treaty of Chicago in 1833, by which the tribe ceded its lands in Illinois, most of the Potawatomi people were removed to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Many perished en route to new lands in the west on their journey through Iowa, Kansas, and Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), following what became known as the " Trail of Death".Language

Potawatomi (also spelled Pottawatomie; in Potawatomi ''Bodéwadmimwen'' or ''Bodéwadmi Zheshmowen'' or ''Neshnabémwen'') is aCentral

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

Algonquian language spoken around the Great Lakes in Michigan and Wisconsin. It is also spoken by Potawatomi in Kansas, Oklahoma, and southern Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

. Fewer than 1300 people speak Potawatomi as a first language, most of them elderly. The people are working to revitalize the language.

The Potawatomi language is most similar to the Odawa language

The Ottawa, also known as the Odawa dialect of the Ojibwe language is spoken by the Ottawa people in southern Ontario in Canada, and northern Michigan in the United States. Descendants of migrant Ottawa speakers live in Kansas and Oklahoma. Th ...

; it also has borrowed a considerable amount of vocabulary from Sauk. Like the Odawa language, or the Ottawa dialect of the Anishinaabe language

Ojibwe , also known as Ojibwa , Ojibway, Otchipwe,R. R. Bishop Baraga, 1878''A Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language''/ref> Ojibwemowin, or Anishinaabemowin, is an indigenous language of North America of the Algonquian lan ...

, the Potawatomi language exhibits a great amount of vowel syncope.

Many places in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

have names derived from the Potawatomi language, including Waukegan

''(Fortress or Trading Post)''

, image_flag =

, image_seal =

, blank_emblem_size = 150

, blank_emblem_type = Logo

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_type1 = State

, subdivisi ...

, Muskegon

Muskegon ( ') is a city in Michigan. It is the county seat of Muskegon County. Muskegon is known for fishing, sailing regattas, pleasure boating, and as a commercial and cruise ship port. It is a popular vacation destination because of the expan ...

, Oconomowoc

Oconomowoc ( ) is a city in Waukesha County, Wisconsin, United States. The name was derived from Coo-no-mo-wauk, the Potawatomi term for "waterfall." The population was 15,712 at the 2010 census. The city is partially adjacent to the Town of Oc ...

, Pottawattamie County

Pottawattamie County () is a county located in the U.S. state of Iowa. At the 2020 census, the population was 93,667, making it the tenth-most populous county in Iowa. The county takes its name from the Potawatomi Native American tribe. The co ...

, Kalamazoo

Kalamazoo ( ) is a city in the southwest region of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the county seat of Kalamazoo County. At the 2010 census, Kalamazoo had a population of 74,262. Kalamazoo is the major city of the Kalamazoo-Portage Metropolit ...

, and Skokie.

Potawatomi people

* Ron Baker: played for the New York Knicks and the Washington Wizards. *Charles J. Chaput

Charles Joseph Chaput ( ; born September 26, 1944) is an American prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He was the ninth archbishop of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, serving from 2011 until 2020. He previously served as archb ...

(born 1944 - son of a Potawatomi woman): Catholic Archbishop of Philadelphia

The Roman Catholic Metropolitan Archdiocese of Philadelphia is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in southeastern Pennsylvania, in the United States. It covers the City and County of Philadelphia as well a ...

from 2011 to 2020.

*Kelly Church

Kelly Jean Church ( Match-e-benash-she-wish Potawatomi/ Odawa/Ojibwe) is a black ash basket maker, Woodlands style painter, birchbark biter, and educator.

Background

Kelly Church, a fifth-generation basket maker, was born in 1967. She grew up ...

(Potawatomi/Odawa/Ojibwe): basket maker, painter, and educator.

*Robin Wall Kimmerer

Robin Wall Kimmerer (born 1953) is an American Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental and Forest Biology; and Director, Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, at the State University of New York College of Environmental Scien ...

: botanist and writer - author of ''Braiding Sweetgrass

''Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants'' is a 2013 nonfiction book by Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Potawatomi professor Robin Wall Kimmerer, about the role of Indigenous knowledge as an alternat ...

''.

*Simon Pokagon

Simon Pokagon ( 1830- January 28, 1899) was a member of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, an author, and a Native American advocate. He was born near Bertrand in southwest Michigan Territory and died on January 28, 1899 in Hartford, Michig ...

: the "Hereditary and Last Chief" of the Pokagon Band.

*Leopold Pokagon

Leopold Pokagon (c. 1775 – 1841) was a Potawatomi ''Wkema'' (leader). Taking over from Topinbee, who became the head of the Potawatomi of the Saint Joseph River Valley in Michigan, a band that later took his name.

Early life and education

Po ...

: head of the Potawatomi in the Saint Joseph River Valley.

*Jeri Redcorn

Jereldine "Jeri" Redcorn (born November 23, 1939) is an Oklahoman artist who single-handedly revived traditional Caddo pottery.

: the Oklahoman artist who revived traditional Caddo pottery.

* Topinabee: head of the Potawatomi of the Saint Joseph River Valley.

*Stephanie "Pyet" Despain: winner of the cooking competition, ''Next Level Chef

''Next Level Chef'' is an American reality television series that premiered on Fox on January 2, 2022. The series is hosted by Gordon Ramsay, who also serves as a mentor along with Nyesha Arrington and Richard Blais.

In March 2022, the series ...

''.

See also

*Cherokee Commission

The Cherokee Commission, was a three-person bi-partisan body created by President Benjamin Harrison to operate under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889. Sec ...

* Nanabozho

In Anishinaabe ''aadizookaan'' (traditional storytelling), particularly among the Ojibwe, Nanabozho (in syllabics: , ), also known as Nanabush, is a spirit, and figures prominently in their storytelling, including the story of the world's creat ...

* Theresa Marsh

Theresa Marsh is located near Theresa, Wisconsin, in northern Washington County and eastern Dodge County. The marsh is the starting point for the Rock River, a tributary of the Mississippi River, and the marsh is an important stopping point for ...

* Treaty with the Potawatomi

During the first half of the 19th century, several treaties were concluded between the United States of America and the Native American tribe of the Potawatomi. These treaties concerned the cession of lands by the tribe, and were part of a l ...

References

External links

*Hannahville Indian Community; Wilson, MI

Citizen Potawatomi Nation

official website

Forest County Potawatomi

Kettle & Stony Point First Nation

Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi

(Gun Lake)

Moose Deer Point First Nation

Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

Potawatomi Author Larry Mitchell

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

Treaty Between the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi Indians

Potawatomi Migration from Wisconsin and Michigan to Canada

{{authority control Algonquian peoples Great Lakes tribes Native American tribes in Kansas Native American tribes in Illinois Native American tribes in Michigan Native American tribes in Wisconsin Native American tribes in Oklahoma Algonquian ethnonyms Native American tribes in Indiana Native American tribes in Nebraska